V, XXII: The Eight Principles of Liberal Democracy

In contrast to the Unionist Party, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) was a federal organization comprising different organizations around the Union. Despite this, its organisation leaned heavily on the experience of mass movements. The experiences of the mass congresses of the Democratic Federation influenced the leaders of the party immensely. To channel this into effective policy-making, the LDP Parliamentary Committee called a congress for October 1891 in Newcastle.

Despite this, the party's parliamentary leader, William Harcourt, came from the Liberal faction and had no time for mass politics. Harcourt stated his intention to miss the congress, an incredibly controversial act. He believed that the parliamentary committee should lead the policy debate and saw no role for members in party decision-making.

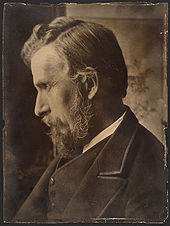

William Harcourt, first Leader of the LDP (1889-92)

This clash between the membership and leadership weakened the ability of the LDP to advocate for its beliefs to the wider public. Harcourt did not connect with the public, either. He was considered smart but cold and aloof and didn't have the political presence of Chamberlain, Churchill, or other senior Unionists. The defection of the Unionists from the Democrats had robbed the opposition of all of its most pertinent weapons.

Still, the Parliamentary nous of Harcourt made him a valuable asset, as did his intellectual might. He was a supreme orator and commanded a personal following in the Commons that few could match. Outside of the debating chamber, he was of little use as a leader. Similarly, many of the most prominent Liberal Democratic leaders, like Herbert Gladstone and Davitt, had little experience in Parliament, thanks to their backgrounds in state politics.

Harcourt was the most capable Parliamentarian that the group had in the House of Commons. His support would be crucial to its success. He finally agreed to attend the Congress and preside over its opening session around four weeks before it began. The Second LDP Congress needed to settle three issues. Firstly, it needed to agree on a party structure; secondly, it needed to appoint a leader; third, it needed to adopt a platform to unite the party. The Congress consisted of a delegation from member parties, nominated at individual party congresses in the leadup to the main party congress.

The assembly approved a drafting committee to decide on a party structure, which produced a proposal that the broader Congress accepted. It placed the Congress at the centre of the governing structure, with the right to elect a President, the Chief Executive Officer of the Federal Party. The congress would also elect a 30-man Executive Committee overseeing the party's day-to-day running between congresses.

A motion agreed upon by the congress ensured that the three elements of the party (municipal, state, and Parliamentary) would each have representatives on the Committee, and at least one member would represent each component party. Harcourt was elected President of the LDP at the Congress but was severely restricted by a radical Executive Committee that featured many National Democratic and Fusionist members. Francis Schnadhorst chaired the Executive Committee, a key advocate of the mass movement faction within the party, and its secretary was Henry Campbell-Bannerman, a traditional radical.

Concerning the party platform, the Executive Committee used the Congress to adopt two separate mission statements. One would be a general statement of aims, the other a more concrete policy 'shopping list.'

The general aims would be debated and added to the party constitution at the beginning of the Congress; members would then decide on the shopping list with an omnibus resolution at the end. The Executive Committee members hoped Harcourt would accept the omnibus resolution and make it part of the program. If he were not, the general aims would protect them. The Statement of General Aims is still a part of the LDP Constitution (although its application is iffy at best). The document is known as the "Eight Principles of Liberal Democracy."

The first aim would be the complete separation of church and state, with all subsidies and state control of the Church of England (C), ensuring that all religious groups were equal in the law. The second was Republicanism, and Harcourt delivered a speech at the conference confirming that should the LDP form the next government, it would bring forward legislation to abolish the regency and declare a Republic.

Third was pluralism, where multiple nationalities could co-exist within the Union. The fourth, populism, states people should be the ultimate driver of political action. The fifth principle was reformism, resisting violent revolution and working within the Parliamentary system to achieve their goals. The sixth principle was pacifism and opposition to war. Finally, the old Georgist calls for Free Trade and Free Land were the seventh and eighth principles.

As Executive Committee members were sworn in, Harcourt, as President, asked each to swear loyalty to the constitution and the founding principles of the Liberal Democratic Party. Each of the main factions was represented in its contents and mutually agreed to the remainder of the principles. A ninth principle of Solidarism would be eventually added in 1896, but we’ll get to that. One of the Executive Committee members, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, summed up the party's principles in a simple phrase; 'freedom of trade, freedom of land, and freedom of life.'

Secondly, the Congress drafted an omnibus motion to show support for various motions that formed what would be known as the 1892 Newcastle Programme, one of the first 'manifestos' of sorts in the Union.

The headline proposal was the commitment to abolishing the regency, its lands, and property, and declaring a republic with a President elected by the Grand Committee. Campbell-Bannerman called the Regency "a model of outdated nostalgia for a life not lived in reality." Republicanism united the whole party, even those who had traditionally been part of the Monarchist Liberal party.

On agricultural affairs, the LDP sought compulsory powers for States to acquire lands for small holdings, village halls, and labourers dwellings, a policy to turn rural workers into small-scale co-operative tenants. But the Party also sought a comprehensive national land value tax, freedom for tenants to sell holdings, and compensation for disturbance and improvement. These proposals attracted considerable opposition from aristocratic landlords, who began to fund the Unionist Party.

The party proposed disestablishing the Anglican Church in line with its secularist principle, removing their legal privileges and putting them on the same footing as other protestant sects while removing their influence from education. In addition, there would be a state commitment to a direct popular veto on the liquor trade and localised prohibition of alcohol to stem what the temperance movement condemned as a cause of poverty. Members also passed motions protecting the States' rights from central government, like allocating national matters such as calling an emergency subject to Grand Committee approval.

Electoral reforms were among the most developed of the Newcastle policies. Nationally, reform would secure faster registration of those who moved home and abolish plural voting. These proposals would diminish the power of larger property owners. The state would also pay MPs to encourage more working-class candidates, and the State would transfer the cost of polling from the candidates to the consolidated state funds.

The Congress also debated the direct election of the Senate and Lord Lieutenants, but a slim majority of members defeated this measure. The party also declared its support for a meritocratic society, and wanted to double down the pursuit of sinecure positions from across the civil service, something only halfheartedly engaged with by the Unionists.

From a forward-thinking policy standpoint, the LDP also supported linguistic reform to allow for national languages to be taught in schools. Pluralism was critical to the party's appeal in the Celtic nations. Michael Davitt announced his return to front-line politics with a landmark speech on the linguistic politics that would eventually form the basis of the foundation of the Gaelic League in 1893. Another essential policy emphasized judicial reform, proposing to simplify the Union courts and create an Independent Supreme Court nominated by the President-Regent and approved by a sitting of the Grand Committee.

Chamberlain painted the LDP as a rehashing of Gladstonian Liberalism, the party controlled by the old Liberal elite, and said the programme and its aims were a ‘conglomerate,’ an ‘undigested policy’ that would ‘crumble to pieces from its own weight.’ He also decried it as pure and simple faddism. He joked about the LDP's secretary, his former ally, Francis Schnadhorst, that 'if any man had a fad, let him write to Mr. Schnadhorst.' Schnadhorst would 'put into his programme something he thought likely to tickle the ears of every class.' Senator Cecil joined the criticism and said it was ‘capsules made up in gelatine, in which very nasty stuffs are enclosed’ when asked about the programme in the Carlton Club.

Unionist cartoon deriding the Liberal Democratic Party, 1892 Election

Despite the howls from the Unionists, the party's rank-and-file members supported the program and found it ‘desirable that a broad and far-reaching platform should be outlined.’ Campbell-Bannerman declared the country was ‘indebted to the Liberal Democratic Party for selecting and cataloging those reforms which are most urgent, and thus indicating, far in advance of legislative action, the path to be traversed.’

Others called the Congress a sign that the LDP was ‘a triumphant army marching to almost certain victory.’ The program was popular, and numerous LDP branches were formed nationwide in the aftermath of the Congress. On Harcourt's route back to London, he was swamped with messages of support. For example, a letter from the Darlington LDP, formed in the aftermath of the Congress, said, ‘we will place you in power with a large majority to aid you in passing many important measures in the Newcastle Programme.’

Popular support and excitement grew for the prospects of the LDP, but the most important element of the Newcastle Programme was its precedent for major political parties using ordinary members to participate in policy development. It built upon the Unionist First Programme to develop the notion that a political manifesto is essential in presenting a party as a viable alternative constructive government.